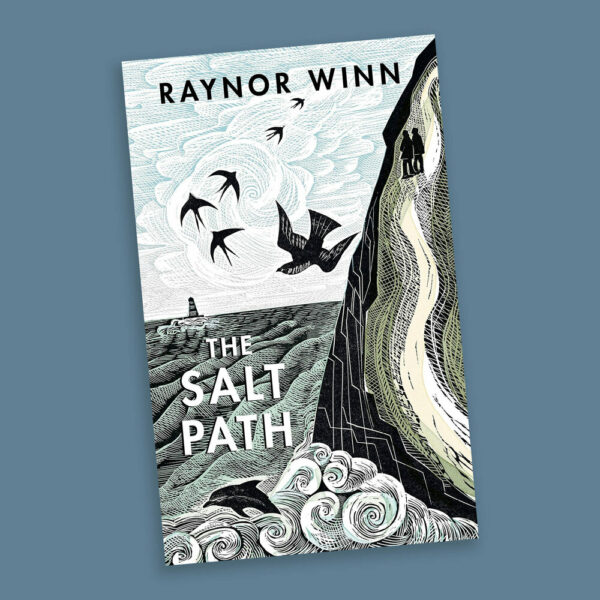

I’ve always had my doubts about *The Salt Path*, as anyone who has spoken to me about this book knows. There was something that niggled away at me. Now, after The Observer’s excellent investigation, I could feel vindicated, but I actually just feel frustrated.

It’s very much worth a read in The Observer online, where journalist Chloe Hadjimatheou has done what I suspect many secretly wondered about but never dared voice: she dug into the real story behind Raynor Winn’s bestselling memoir. Her piece makes for uncomfortable reading. I’d love to know how it came about that she looked into this.

So, what’s not true? Well, the vague explanations about losing their house? Not for the reason they said. And Sally Walker (Winn’s real name) allegedly embezzled over £60,000 from her employer. The heartbreaking homelessness narrative? They owned property in France. The devastating diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration that formed the emotional core of the story? Nine neurologists told The Observer they doubt Moth (real name Tim) could have lived so long or so well with that condition. I confess I have Googled him twice a year since I read it, to see how he’s doing. Not that I wish him ill, but he seemed to be doing remarkably well.

As I wrote on Instagram when the story broke: “Memory is a fickle fish, and memoir is about emotional truth of course. But telling porkies for profit, creating a worthy and ‘inspiring’ public

persona, and taking a publishing place that could have gone to someone authentic, is not bloomin’ well on.”

What makes this particularly infuriating is how it reflects on a genre I absolutely love. Memoir has the power to connect us, to show us resilience in the face of adversity, to offer hope when we need it most. When someone manipulates that trust, it damages the entire genre and makes readers more sceptical.

Think about the people who felt genuinely inspired by this story – the readers who saw themselves in Raynor and Moth’s struggles, who found comfort in their journey, who maybe even attempted their own version of the salt path. Maybe even walked the actual path! Now they feel cheated, and rightly so. The emotional investment readers make in memoir is profound

because we believe we’re connecting with real human experience.

We read memoir to learn how to survive. At least that’s why I read memoir. And yes, I could get the same thing from a novel. But I cleave to memoir because it’s real. This one was wrapped in just too shiny a bow, though.

(Sadly, this isn’t the only memoir I know about that isn’t quite true – and I hope those come to light in time.)

There’s a difference between the inevitable gaps and reconstructions that happen when we’re working with memory – we all understand that conversations can’t be remembered verbatim, that time compresses and expands in our recollection, that sometimes no matter how hard we try, we can’t recall. But that’s okay, and we can even explain this to our readers in our role as narrator (in memoir we can be the narrator as well as the main character). But there’s a massive difference between that and what appears to have happened here, in my opinion.

The publishing industry needs to ask itself some serious questions. How did this get through? Were the right checks done? When a story seems too perfect, too inspirational, too much like exactly what readers want to hear, shouldn’t that trigger some investigation rather than just

enthusiastic marketing?

It’s not about being harsh on authors who get details wrong or misremember events. It’s about the deliberate construction of a narrative that appears to be fundamentally dishonest. When you’re asking people to invest emotionally in your story, when you’re presenting yourself as someone who has suffered and triumphed in ways that inspire others, you have a responsibility to be truthful.

The saddest part? There are incredible, authentic memoirs out there that deserve this level of attention and success. Stories of real resilience, real triumph, real human experience that don’t need embellishment because the truth is powerful enough on its own.

As someone who works with people telling their own stories, I know how hard it is to get the balance right between being honest and being readable, between protecting people’s privacy and giving readers enough context to understand what happened. But that’s the work – the real work of memoir. Not creating a marketable fiction and selling it as truth.

(I once abandoned a ghostwriting project when I realised what the author was telling me wasn’t true.)

The genre will survive this, as it has survived other controversies. But each time something like this happens, it makes the path (!) a little harder for the genuine voices. It diminishes the beautiful connection between memoirist and reader. And it makes readers like me who are grateful to the courageous memoirists of the world who are imparting their wisdom to make life a little easier for the rest of us, a little bit suspicious in a world where it can be hard to know who to believe. A world where I believe in memoir and memoirists! And that, quite frankly, makes me furious.

I’ll be interested to see what happens next. But at least I no longer have to Google the husband.